The ghost in the machine

There were still weekends for surfing

There is one thing about writing your first novel that is brilliant: no one, least of all you, has any expectations about the outcome. Oh sure, you’re hoping you’re writing a book that will get published, get rave reviews, maybe even be a bestseller. But that’s a secret hope as you sit at the laptop putting those sentences up on the screen. And that’s the best it is ever going to be if you become a published writer.

Okay, these days that sense of being alone at the coalface can be slightly different. On my WriteOnline Masterclass each year there are some thirty writers willing to let me see (and comment on) what they’re writing. But at that stage, for most of them, I’m the only reader. And I’m digital - the ghost in the machine. Most of these writers I’ve never met so I really do exist for them as a figment of their imagination. Or that’s how I think of it.

With my first novels - the five I dumped and the sixth that made it - Jill, the Red Pen Editor, knew I was writing but she had no idea what the story was about or what sort of characters were in it. So, for those years, mid-1985 to early 1988, while writing No 6, it was just me and the characters: Captain Nunes, his daughter Frieda, and a bunch of misfits from Lady Sarah, to Vygie Bond, Mondling, Jong Jan, Mad Minnaar, Marsdon Beg-rip, Montague Planke, Fagmie Jabaar, Boatswain Baleen, Namaqua Drift, and some other minor walk-ons. I was having a great time and the best thing was that it was just me and these weirdos. And there were no outside expectations.

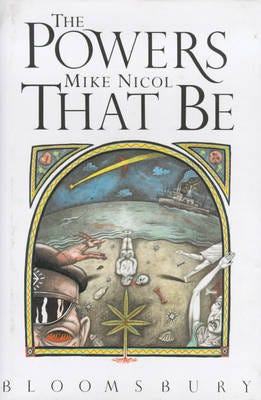

Through 1985, I worked at Creda Press editing, proof-reading and writing two newsletters for the company. It was an easy job to handle and I often thought it was bossman Dennis Nick’s way of helping me out of hard times. Meanwhile in my lunch hours and on the train from home in Muizenberg to town and back again, I would write what came to be The Powers That Be. At the end of 1985, Dennis engineered for me to meet Hugh Murray who was moving his magazine, Leadership, to Cape Town and was looking for a journalist. Murray took me on and the novel continued to grow throughout the year, without doubt benefiting from the closer exposure I now had to the politics of those turbulent years. Of course, there were still weekends for surfing.

In mid-1987, Leadership was going through tough financial times and I was fired. At least that was the reason I was given. It turned out to be a good move because it forced me to make my own way. Thing was that Leadership then gave me tons of freelance work and I ended up earning more money than I would have as a paid staffer. More importantly, the freelance work put me onto the streets of the burning townships, got me close up with the strikes and the fiery unrest roiling over the country. Much of that went into The Powers That Be.

In the wintery month before Murray ‘let me go’ - as they say these days - Christopher Hope dropped me a postcard to ask if I would meet with his London agent, Hilary Rubinstein, who had come out to South Africa on a ‘working’ holiday as Nadine Gordimer was also one of his clients. Rubinstein was at the Mount Nelson, so late one cold and wet June afternoon I rocked up to have a drink with him. I can’t remember what we talked about - probably the state of the country as a state of emergency had been declared - but I do remember that he’d just taken a dip in the swimming pool which I thought was completely nuts. I also remember that as I was leaving, I tentatively told him I was writing a novel and could I send it to him when I’d finished. It was a cheeky request but being a gentleman he replied, ‘Of course’, probably never expecting to be taken up on the offer.

Come January or February of 1988 I finished the book and got a faint dot-matrix printout. It made the story look completely insubstantial which was concerning. With much nervousness, I gave this to Jill to read. A few days later she said, ‘I think you’ve written a novel.’ Those are the words writers want to hear but fear will never be uttered.

What followed happened at speed. The manuscript was posted to Hilary Rubinstein at A P Watt (in those days we had a postal system). He had a new assistant, one Clarissa Rushdie. (Yes, she had been married to Salman Rushdie.) She liked the book and took it to Liz Calder at the newly established Bloomsbury. (Liz had once shared a house with the Rushdies.) Bloomsbury bought the book within weeks and Liz contacted her friend Gary Fisketjon at Atlantic Monthly in New York, and within a few more weeks he had phoned to say he would publish as well. Publication date was set for April 1989. But before that came the Frankfurt Book Fair in October 1988 where the book went on auction - a magic moment for all authors when agents are actually bidding for your work - and a number of foreign publishers bought into the rollercoaster.

During the second half of 1988, I had been re-employed as a sub at Leadership. Also on the magazine was Dene Smuts and I remember confiding in her about this mad, strange world that had suddenly entered my life. Because while all this was going on, Secker & Warburg had contacted me about writing a book about the Drum journalists of the 1950s. I decided I would resign from Leadership in the new year and take my chances with the vagaries of the world. As it happened Dene was of like mind.

‘I’ll bet I leave before you do,’ she said.

She won and went off to a political career two months before I left to start the quest for the remnants of the golden age of the Drum journalists.

Thanks for being the ghost in my machine - that’s exactly how I imagine you. I’m probably more familiar than I should be given that we’ve never met. But you’re like a second voice in my head as I’m writing.

Also, your career as you’re sharing it here, slowly but surely, is just fascinating.

Maybe some of us never hear those magic words, you've got a novel, but still we pursue because writing is just part of who we are and what we enjoy. Till then, the next sentence awaits.