Getting to interview Esme Matshikiza for my book on Drum was “interesting”. Because the widow of legendary Drum writer and creator of the hit musical, King Kong, Todd Matshikiza was, to say the least, offish. Jurgen Schadeberg had given me her London phone number, and he’d issued a cautionary.

‘You’ll need to convince her that you’ve spoken to me and that I gave you her number,’ he had warned. ‘You’ve got to understand people are jumpy when South Africans phone them out of the blue.’

He was right. On the phone Esme was cautious. But then who wouldn’t be? It was April 1989. Most political prisoners in South Africa might have been released, change was in the air, but I could have been a BOSS agent (Bureau of State Security) out to cause mischief. So she was hesitant. But eventually she agreed to meet me at a cafe in the South Bank complex. Which, my memory has it, was a ghastly place of dank concrete.

The Matshikizas had been living in the UK since 1960. The following year, Todd brought King Kong to the London stage. It was based on the life of a heavyweight boxing champion, Ezekiel Dhlamini, known as ‘King Kong’ and one of the folk heroes of the 1950s. In Johannesburg King Kong had played to rapturous applause. As it did when staged in the West End and Broadway.

Todd Matshikiza was one of the stars of Drum. A musician by temperament he also turned his writing into music. His musical career had taken off in 1956 when he was commissioned to compose a cantata for Johannesburg’s seventieth anniversary the next year. It was called ‘Uxolo’ (Peace), and, in seven fragments played out by a seventy-piece brass orchestra and two hundred voices, told the story of a city founded on gold and riddled with racial strife. It ended with a prayer for peace. The concerts were sold out: people stood in the aisles and on the steps outside. They couldn’t get enough.

Given this, the King Kong success, and the stories he’d written for the magazine, Esme Matshikiza was a necessary voice in my book, a valuable insight into the world of her husband and Drum magazine. So I was really keen to have her agree to an interview.

Whatever happened at our first meeting over bad coffee at the South Bank, whatever I said, persuaded her to take a chance. The next week we met at her flat, where this elegant woman was gracious, lively, witty, full of the sort of stories I wanted to hear.

Esme Matshikiza: “Todd handled society, the apartheid laws, with a mixture of amusement and very strong criticism. A lot of it he found amusing, but amusing in a satirical way. Just as his writing is very satirical. That was his approach to South Africa. It did hurt, but he had so much inborn faith in himself and who he was and where he came from that he was extremely self-confident about being a South African.”

On shebeens and drink: “I never went to shebeens, but Todd certainly did. I don’t think he ever played [music] in a shebeen but he certainly would go there to drink and came back with wonderful stories which he wrote about. I mean life seemed to have happened in the shebeens. [Todd] did drink, but I never actually saw [him] drunk. He died of liver failure, but nobody can ever tell you he got drunk. He was such a small person and a difficult eater, possibly because he drank too much. The drink was a defence against everything that happened to you if you were black in South Africa and especially if you were in the front line like his generation of journalists was. Once we’d [become UK citizens] we realised there was no going back, and in fact Todd never went back. By the end of his life he was a very sad man. He really wanted to go home again.”

But he couldn’t. By then he had been banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. In the latter half of the 1960s, Todd Matshikiza tried to get as close to his home country as he could by working on radio stations in Malawi and Zambia. But that was the nearest he got: he died in Lusaka in 1968. Fourteen years later his autobiography, Chocolates for my Wife, was finally unbanned in South Africa.

One of the bands Todd Matshikiza wrote about was the Merry Blackbirds. He called them “The greatest ballroom-dancing and swing band. The best band in Johannesburg.”

Here’s how he began a piece Drum published in September 1954:

The hall was chock-full of people. The hall was chock-full of music. It was good music from Peter Rezant and this famous Merry Blackbirds. I said to the fellow next to me, ‘What do you think of this fellow, Peter Rezant?’ The fellow next to me said, ‘Man, firs’ class.’

I crossed the floor and asked a lady, ‘What do you think of P-?’

She didn’t let me finish. ‘Firs’ class, firs’ class. Couldn’t be nothing better nowhere.’”

A year before that article he’d written a piece on how musicians died.

It began: “Some are stabbed, some are burned, some just vanish. If you ever wished you were a famous musician, you might as well wish you were a circus clown. But of course you’ve never given a moment’s thought to the private life of a circus clown.

“If I tell you now that these people have great fears that stalk their puny lives like a hunter stalks a rabbit, you’d be surprised.”

It ended: “We musicians and clowns can never tell the manner of our death. The happiness of a secure and sheltered life is not for us. We die by your hand, by violence. Sometimes among friends, most times not. Like Stephen Monkoe, the champion trumpeter of the Merry Blackbirds, or Arrah Lefatula, the dancing star of the Pitch Black Follies. They both died in prison cells where fate had flown them ... far from friend or family.

“The price of musical fame is the price of your life. So if you still want to be a famous musicians, you know the price that many of us have paid.”

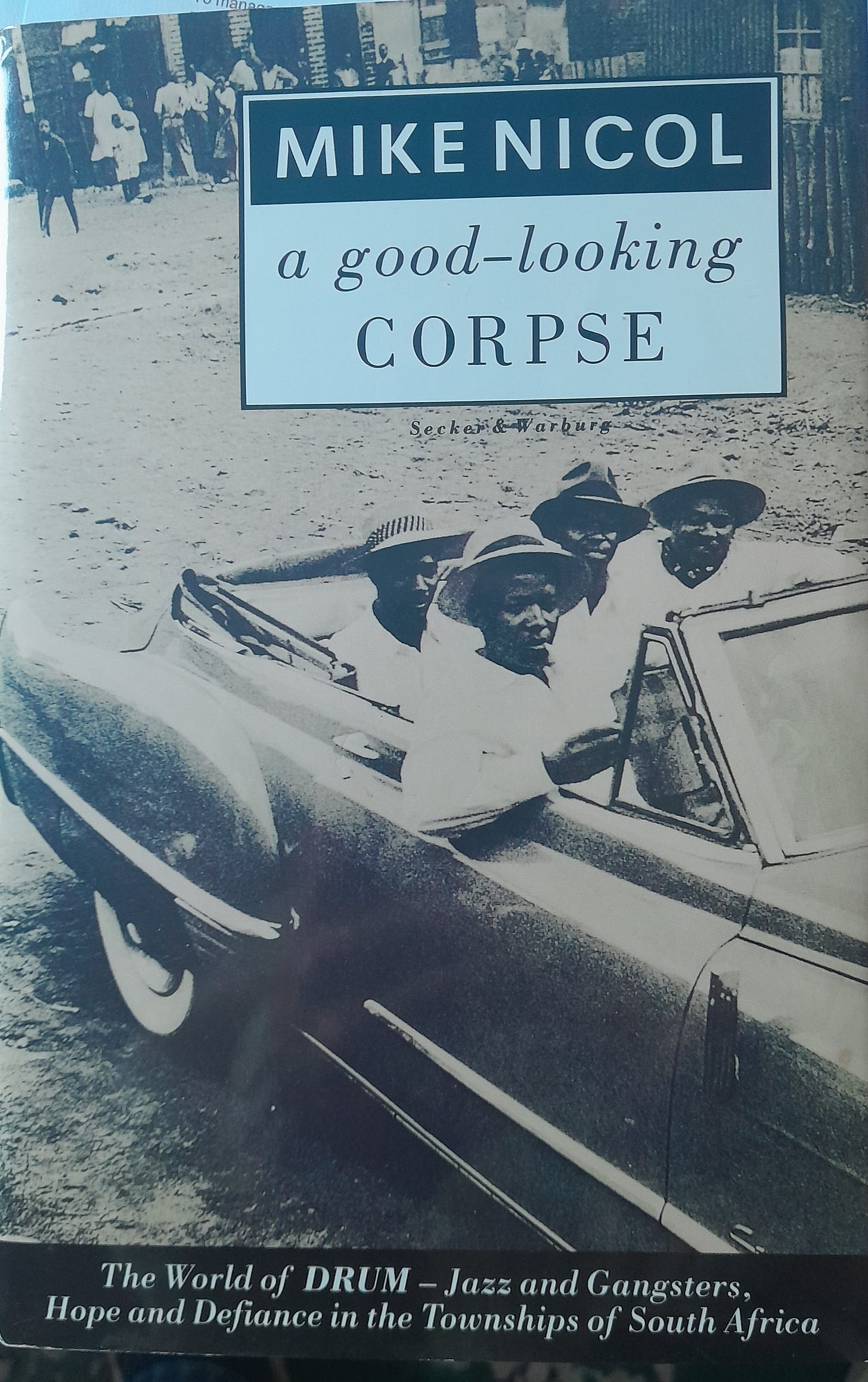

You can buy the digital version of A Good-Looking Corpse here.

If i'm not mistaken, I found the ‘Uxolo’ record in my parents' collection when I was last down. I was fascinated by the cover and the date. Didn't have an LP player though, so couldn't hear it.